Cancer virus discovery helped by delayed flight

- Published

Bad weather and a delayed flight might be a recipe for misery - but in one instance 50 years ago it led to a discovery that has saved countless thousands of lives.

The discovery of the Epstein Barr virus - named after British doctor Anthony Epstein - resulted from his specialist knowledge of viruses which caused tumours in chickens plus his skills gained using one of the first commercially-available electron microscopes.

His hunch was assisted by a longer than expected journey of some tumour cells from Uganda, which were nearly thrown in the bin.

But it would never have happened if Epstein's curiosity hadn't been fired up by a lecture by the Irish doctor turned "bush surgeon", Denis Burkitt.

In the lecture, billed as a staff meeting on "The Commonest Children's Cancer in Tropical Africa", Burkitt described how he had noticed a number of cases of debilitating tumours which grew around the jawbone of children in specific regions - particularly those with high temperatures and high rainfall.

We now know this as Burkitt lymphoma.

Sir Anthony Epstein, now 93, speaking to the BBC's Health Check programme, recalls: "I thought there must be some biological agent involved. I was working on chicken viruses which cause cancer. I had virus-inducing tumours at the front of my head. I thought... [it] was being carried by some insect vector, or some tic. That's why it was temperature-related."

The Epstein Barr virus belongs to the family of herpes viruses - and is linked to a number of different conditions, depending on where you live.

Most people are infected with the Epstein Barr virus. It's best known in high-income countries for causing glandular fever which causes a sore throat, extreme fatigue and swollen glands in the neck.

According to Dorothy Crawford, emeritus professor of microbiology at Edinburgh University, up to 95% of all adults are infected with the virus.

"The virus is spread in childhood at different rates - in the saliva, so through close contact. In African countries most children have it by the age of two because they share cups in their household.

"The rate is lower in middle-class areas of England, so if you haven't already been exposed by your early teens it can cause glandular fever."

This has given it the nickname the kissing disease because, she explained: "People kissing in the back row of the cinema exchange more saliva than young children sharing toys."

Epstein asked for samples of the tumours from Burkitt and they were sent back on overnight flights from Uganda.

For almost three years Epstein's efforts to retrieve virus from the tumour cells failed, despite trying several culture methods used successfully for other viruses like influenza and measles.

In the end bad weather came to the rescue.

Fog delayed one flight which was diverted to Manchester, 200 miles from London. So the sample taken from the upper jaw of a nine-year-old girl with Burkitt lymphoma didn't get to Epstein until late one Friday afternoon on 5 December 1963.

At that point it looked past its sell-by date.

"The fluid was cloudy. This suggested it had been contaminated on the way," Epstein said.

"Was it full of multiplying bacteria? Before we threw it away I looked at it under a wet preparation microscope and saw huge numbers of free-floating, healthy looking tumour cells which had been shed from the edge of the tumour."

Traditionally, growing cells successfully in culture had involved sticking them to a glass surface for support, but the lymphoma cells seemed to favour growing in a suspension.

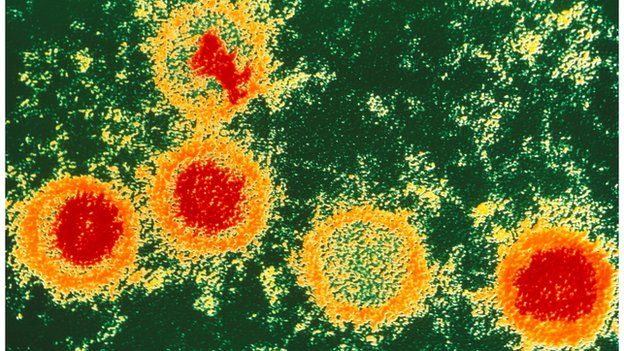

Once all other conventional tests for identifying the virus from the cultured cells had failed, Epstein tried electron microscopy. The very first grid square he viewed included a cell filled with herpes virus.

Exhilarated by what he'd seen, Epstein went for a walk in the winter snow and came back feeling calmer.

"I was extremely frightened in case the electron beam [of the microscope] burned up the sample. I recognised at once the herpes virus - there were five then, now nine. Any of the then-known ones would have wiped the culture out when they were replicating but this wasn't happening. I had the feeling that this was something special."

Our understanding of this pervasive virus, named after Epstein and one of his PhD students Yvonne Barr who helped to prepare the samples, has increased over the years since Epstein confirmed his findings with American virologist colleagues.

Burkitt's data helped to identify that the tumour named after him was seen in children with chronic malaria, which reduced their resistance to the Epstein Barr virus, allowing it to thrive.

But most of us live quite happily with the virus.

"If you disturb the host-virus balance in any way then changes take place which lead to very unpleasant consequences," says Epstein.

"Once the link between Epstein Barr virus and Burkitt lymphoma was established, other seemingly unrelated conditions followed. These include a cancer at the back of the nose which is the commonest cancer seen in men in southern China and the second commonest in women in the same region.

There is also a link to Hodgkins lymphoma, a cancer of the white blood cells.

"Each one came out of the blue," according to Epstein, "and we've just heard about another. About 20% of Japanese cancers of the stomach are associated with the virus."

Yet another connection was made by Professor Dorothy Crawford, while waiting for the lift at the Royal Free hospital in London.

"It's such a tall building everyone meets outside the lifts. I was standing next to a renal [kidney] transplant surgeon and overheard him say they'd just had their first case of post-transplant lymphoma. So I went with him to the pathology department and asked for some sections of the tissue to look at under the microscope."

Burkitt lymphoma can now often be treated successfully with chemotherapy.

At a recent meeting in Oxford of the Epstein Barr Virus Association future directions for research were explored.

Attention is now focusing on a vaccine for the Epstein Barr virus - and some efficacy has already been demonstrated.

Epstein hopes that a vaccine will lead to the kind of success seen in other cancers caused by viruses - such as Hepatitis B and the human papillomavirus, which cause liver and cervical cancer respectively.